I recently published an article in a newspaper about Gloria Richardson, a leader in the civil rights movement who passed away in July. Frankly, I’d not thought about that piece until I received an email from the paper’s editor while sitting in an airport awaiting a flight back to Georgia. Now attached to his email was a message from a Joseph Fitzgerald, PhD, history professor, Cabrini University, who wanted to talk to me about my article.

A few days later we spoke, and I discovered that he’d published a biography of Richardson. Now in the spirit of truth-telling, since I was so excited to talk with Richardson’s actual biographer, I automatically assumed that he was Black; that is, gulp, until I received his picture. We sometimes fall into the trap of making assumptions, and I’m no exception.

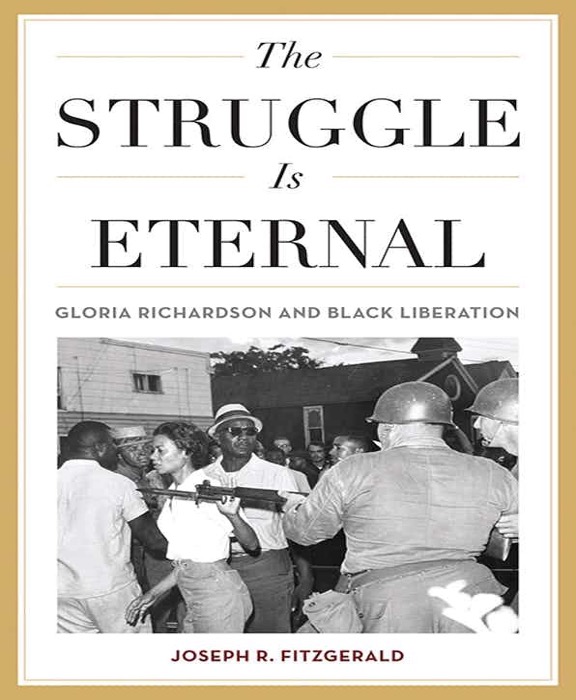

So, my embarrassment aside, I bought his book, decided to do a follow up and asked him to share frequent questions he gets asked about the book and his typical answers. Here they are.

“Why did you write her biography?”

My master’s thesis was on Black women’s contributions to the Civil Rights and Women’s Movements. I profiled seven women, one of whom was Ms. Richardson. I wrote about her work on civil rights. While I was a doctoral student in Black Studies at Temple University, I decided to write Richardson’s biography for my dissertation project because no one had ever given her that level of scholarly attention. Importantly, because she was an intellectual, I needed to show why she did what she did, and that’s why the book is an intellectual history of Richardson. To my surprise, Ms. Richardson told me that I was the only scholar who had ever proposed working with her on a biography.

“How long did this project take?”

From my dissertation phase to publishing the book it took about fifteen years. It was a huge part of my life; the project was all consuming and I loved working it.

“I had never heard about Gloria Richardson. Why don’t more people know about her?”

There are a few reasons. One is that she was active in the Movement for about three full years, much less than some of her comrades such as Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, Martin Luther King, Jr., and others. Additionally, she was leading a movement in Maryland, which is in the upper-south and where Black people did have the right to vote but where apartheid existed in public accommodation. Most civil rights histories focus on more southern locations.

The rise of Black Power is another factor. Combined, the Cambridge Movement, and her leadership of it, serve as a case study in Black Power and they influence its goals, strategies, and tactics. However, Richardson stopped being active in the Movement in 1964 when Black Power was on the ascent.

Even though women were key Black Power strategists, theorists, activists and organizers, its leaders, almost all of whom are men, gained attention from the press which then produce stories that were male-centric. In turn, scholarship on Black Power reinforces this masculine narrative. Yet the last 15-20 years have seen a correction in this narrative, and my book is a part of this correction.[wh1]

“Why should more people know about Gloria Richardson?”

If you want to better understand today’s movement, you need to know about the Cambridge Movement. Its social justice agenda–jobs that pay a living wage, affordable housing, access to comprehensive healthcare, quality public school education–is what Black Lives Matter is focused on. Additionally, Richardson was, in today’s vernacular, “unapologetically Black,” an ethos that grounds Black Lives Matter. She was happy that today’s Black youth are unapologetically Black and this, along with their creative thinking, allows the youth to push the nation forward.

“What are some of the more surprising things you learned when working on her biography?”

Wow. There are so many. One is that she had a great sense of humor. She wasn’t jokey but did enjoy sarcasm and satire. Another is that she knew many famous people, from her Howard University professors (E. Franklin Frazier, Sterling Brown, Alain Locke, Rayford Logan, Ralph Bunche), to James Baldwin, Rosa Parks, Harry Belafonte, Fannie Lou Hamer, Senator Edward Brooke, Diane Nash, Malcolm X. and many others. Her network was a “Who’s Who” of 20th Century Black America.

I close this out with words of wisdom with Fitzgerald in mind:

“The main work of the historian is not to record, but to evaluate; for if he does not evaluate, how can he know what is worth recording?” -Edward H. Carr

So, yours truly is well into his book and can honestly say that Mr. Fitzgerald is indeed a topnotch evaluator and recorder.

Excuse me but I have to get back to Chapter 6.

© Terry Howard is an award-winning writer, a contributing writer with the Chattanooga News Chronicle, The Douglas County Sentinel, The American Diversity Report, The BlackMarket.com, co-founder of the “26 Tiny Paint Brushes” writers’ guild, and recipient of the Dr. Martin Luther King Leadership Award.