We held back the laughter but not the pride as the three rambunctious young boys ambled up and down the bleachers during the basketball game last week before Al, the father of one, sternly admonished them to sit down. And they did.

I’ll get back to that shortly. But first for context here’s a headline from a local paper:

“Teens arrested in the shooting deaths of 12, 15-year-olds…”

Now for me the saving grace is that although I could see the faces in an accompanying photo of the two slain young Black boys, I didn’t know them personally nor their parents. And like anyone I could mouth the usual “my thoughts and prayers” before kicking the proverbial “can down the road” before the inevitable next senseless shooting, grateful in the relief of, “thank God that it was not me or one of mine.”

But I couldn’t that easily shake off the image of the boys in the bleachers or the boys felled by those bullets. Plus, as the proud father of two African American sons and two grandsons, I could not disconnect the dots between the images of those boys and those of my sons and grandsons. For the life of me, I just couldn’t.

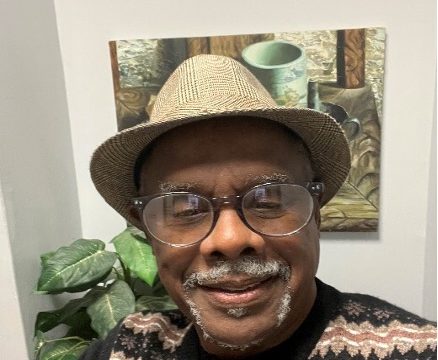

So, I reached out to and sat down with Leonard Jordan and Al Farrell, respectively granddad and dad of two of the boys in the bleachers. I needed to hear their unfiltered perspectives on the realities of being fathers of African American boys these days, to get caught up on their stories and to probe where theirs align with and departs from my own.

“I grew up in Florida and was raised by a mom – and stepfather who I had no emotional connection with – before mom remarried,” said Al. “So I know from experience what it’s like not having a strong male figure in one’s life. That had a strong impact on me.”

Then Leonard, who grew up in rural Tennessee, chimed in. “Although both of my biological parents were present when I grew up, my dad was not a touchy, feely man although he was hard-working and a great provider. In fact, I don’t recall ever seeing him hug my mom or saying “I love you” to any of us. But despite that I know that my life would have been dramatically different without his overall influence on me.”

Shifting gears, I posed this question to the guys: if you could roll back the years to when you were a teenager, what would you do differently based on what you know now?

“Good question,” said Al with a long pause. “Certainly, I would have done a much better job listening to the advice from my mother. I had enough talent to become a professional baseball player but was undisciplined and didn’t listen to my mom like I should have, which allowed other things to get me off track.”

For Leonard his advice would be to accept tough love for his parents, work and study hard and apply the lessons his parents were trying to get through to him at the time. “I realize that tough love can be the best love even if it’s met with resistance and anger.”

I asked them to share their deepest worries about the challenges confronting young Black boys today. Al was the first to respond.

“My biggest concern is gun violence,” he said while pointing to the front-page picture of the two slain young African American boys. “Bullets don’t have a name on them. All it takes is being at the wrong place with the wrong people.” Leonard nodded in total agreement.

Now as both men glanced at their watches so as not to be late for afternoon commitments, I asked them for brief parting messages they’d like to leave with readers, Black dads and boys in particular.

“I say that it’s imperative that parents invest in and stay engaged in their young people’s lives,” said Jordan. “There’s a huge difference between being there with them physically versus being there as a real dad. They need to know that they’re always under a microscope and being watched, especially if they are Black boys.

“Plus, they need to be careful with who they hang out with. So-called friends are not always real friends. Many of those friends will pull the disappearing act if you end up behind bars or stretched out in a coffin.”

“My advice would be for parents to develop strong, visible relationships with their sons’ teachers,” advised Farrell. “That way, those teachers will know that your kid’s performance in school is important to you, and they won’t hesitate to call you if your kid is messing up.”

Al said that he monitors what his son sees in social media even although that may annoy him. “It’s our responsibility as parents to do that. Look, I recently saw one of a 15-year-old boy brandishing a A-15 rifle on a TikTok video.”

“My parting advice is that we let our kids know in no uncertain terms that we expect great things from them and that our expectations are that they carry themselves accordingly,” concluded Jordan.

“Absolutely, said Ferrell. “And I’m not at all ashamed to say that I talk to all five of kids just about every day and always end by saying “I love you” to them.

With that, we agreed that our dialogue was not a one and-done one, fist bumped and went our separate ways before agreeing to meet again at next week’s basketball game, with the three young fellas in tow.

© Terry Howard is an award-winning speaker, writer and storyteller. He is also a contributing writer with the Chattanooga News Chronicle, The American Diversity Report, The Douglas County Sentinel, Blackmarket.com, co-founder of the “26 Tiny Paint Brushes” writers’ guild, recipient of the 2019 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Award, and 3rd place winner of the 2022 Georgia Press Award.