“No one was white before he/she came to America.” – James Baldwin

Before they came to the United States, they were Serbs, Albanians, Swedes, Russians, Turks, Bulgarians, Germans, Italians, etc. Once they arrived, they were all slotted under a new umbrella category….white….and, thus, whether they realized it or not, became part of the dominant caste based on skin color with all its accompanying assumptions, benefits and privileges .

By contrast, a Nigerian-born playwright reported, “You know, there are no Black people in Africa. Africans see themselves as Igbo, Yoruba, Ewe, Akan, Ndebele. They are not Black.” Well, once they and others from the Caribbean arrived in the United States, guess what? – unbeknownst to them they got slotted underneath another umbrella category…..Black…. based on skin color and became part of the bottom rung of the caste system in the United States with all its accompanying disadvantages.

Since the beginning of our republic and massive shifts in demographics, a pathogen has awaken, intact and as powerful as ever….spikes in racial animus and perceived threats to the largely unspoken caste system in this nation under the coded guise of “Make America Great Again.”

With the election of Barack Obama as the first Black president of the United States, we were lulled into a fragile belief of racial progress in just about every field of endeavor, except one – the aforementioned presidency of the United States. What we didn’t anticipate was the seismic response to that moment in history and how it would usher in a man, a movement, an insurrection and book banning feeding frenzies.

Which brings me back to issue of “caste” and where I want to go with this issue in this narrative.

Despite having visited India twice over the years, I hadn’t given the country’s caste system much thought. However, two realities coalesced that got me thinking more and more about caste.

First, I learned that the city of Seattle added caste to the city’s anti-discrimination laws, becoming the first U.S. city to ban caste discrimination and the first in the world to pass such a law outside South Asia. And in 2019, Brandeis University became the first U.S. college to include caste in its nondiscrimination policy followed afterwards by several top notch universities.

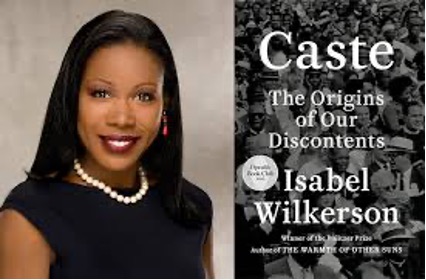

Second, I watched a riveting TV interview of Isabel Wilkerson, author of the book, “Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents” and, before the night was over ordered the book for express delivery.

A pause here and closer look at “caste.”

The origins of the caste system in India can be traced back 3,000 years as a social hierarchy based on one’s occupation and birth. The suffering of those who are at the bottom of the caste pyramid — known as Dalits — has continued. Caste discrimination has been prohibited in India since 1948.

Suddenly the word “caste” has, like Isabel Wilkinson, “lit up my neutrons” with unabated curiosity. On every page of her book, I frequently reread her sentences and paragraphs with a frequent “wow,” “oh my,” “amen,” “yes sir,” here and there, highlighted in yellow key ones and paused to test my comprehension of what she just wrote. Here’s an example:

“Caste is at the infrastructure of our divisions, the architect of human hierarchy, the subconscious code of instructions for maintaining, in our case, a four-hundred-year-old social order. Looking at cast is like holding the country’s X-ray up to the light.”

Now for me, the most compelling – and most disturbing part of the book – resides between pages 39 and 53, a plunge into the brutal realities of America’s “origin sin,” the institution of slavery. Here, Wilkinson writes, “Americans are loath to talk about enslavement in part because what little we know about it goes against our perception of our country as a just and enlightened nation, a beacon of democracy for the world. Slavery is commonly dismissed as a “sad, dark chapter,” in the country’s history. It is as if the greater the distance we can create between slavery and ourselves, the better to stave off the guilt or shame it induces.”

That’s one side.

On the other – this from the perspective of yours truly, a Virginia born African American who can trace his ancestry back to slaves who lived on Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello – those 14 pages were horrifyingly painful and acutely distressful. My yellow page highlighter suddenly fell off to the side in disuse as I struggled with my interest in reading the rest of the book.

Now to bring us to the realities of times we now live in, this explains, in part, the push to “ban” books in a growing number of states to stave off the guilt, shame and embarrassment that history conjures up. Without doubt, among the most daunting tasks for a teacher or parent is to look into the innocent face of a curious student or child and explain to them an institution that made legal the enslavement and brutalization to an entire race of human beings based solely on the color of their skin.

And how do we Black folks, perhaps generations removed from our enslaved forefathers, discuss that sordid history with them without straddling them with a lifetime of insecurity and resentment?

As I write this – although I’m about a third of my way through the book – I needed to step away for it for a while to rethink what I now know and don’t know about caste and race and the interconnection between the two. And that won’t be easy.

In the end, as to the historical importance of the important book, I’ll defer to Oprah Winfrey for the last word:

“Caste” is the most important book I’ve ever selected for my book club. It should be required reading for humanity.” – Oprah Winfrey

I’ll resume reading the book soon. During the meantime, I urge you to snap up a copy before it inevitably ends up on someone’s “ban books” list.

© Terry Howard is an award-winning speaker, writer and storyteller. He is also a contributing writer with the Chattanooga News Chronicle, The American Diversity Report, The Douglas County Sentinel, Blackmarket.com, co-founder of the “26 Tiny Paint Brushes” writers’ guild, recipient of the 2019 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Award, and third place winner of the 2022 Georgia Press Award.