When I got the news that President Biden recently awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to civil rights icon Diane Nash, I called an elated John Edwards, III, publisher of the Chattanooga News Chronicle having recalled a chat I had with him a while ago about his memories of and experiences with Nash.

Said Edwards, whose dad was an influential pastor and civil rights leader in Tennessee, and whose church was bombed by racists, “I was only 12 years old when I got the approval from my father to take part in the sit-ins. Dad dropped me off at the church early each morning where I sat on the front row and took my marching orders from John Lewis and Diane Nash. I was so enamored with those two Fisk University students and the courage they imbodied.”

Diane Judith Nash? Okay, what else don’t we know?

Although not as prominent as others in the American movement for civil rights, Nash’s role and legacy have few parallels. Her campaigns were among the most successful of the era and includes organizing the first successful civil rights campaign to integrate lunch counters in Nashville and spearheading the Freedom Riders to desegregated interstate travel in the south.

“It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Rides to stop after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence,” said Nash in the 2010 documentary Freedom Riders.

Originally fearful of jail, Nash was arrested dozens of times for her activities and spent 30 days in a South Carolina jail after protesting segregation in Rock Hill in 1961. In February that year, she served time in solidarity confinement with the “Rock Hill Nine,” nine students imprisoned after a lunch counter sit-in. They were sentenced to pay a $50 fine for sitting at a whites-only lunch counter. Nash said to the judge, “We feel that if we pay these fines we would be contributing to and supporting the injustice and immoral practices that have been performed in the arrest and conviction of the defendants.”

In 1962, although four months pregnant with her daughter Sherri, Nash faced a two-year prison sentence in Mississippi for “contributing to the delinquency of minors” whom she had encouraged to become Freedom Riders. Despite her pregnancy, she was ready to serve her time with the possibility of her daughter’s being born in jail.

“I believe that if I go to jail now, it may help hasten that day when my child and all children will be free, not only on the day of their birth but for all their lives.” She was sentenced to 10 days in jail in Jackson, Mississippi, where she spent her time there washing her only set of clothing in the sink during the day and, she recalls, “listening to cockroaches skitter overhead at night.”

Shocked by the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham that killed four young girls, Nash and activist James Bevel committed to raising a nonviolent army in Alabama. Their goal was the vote for every Black adult in Alabama, among other southern states that had effectively excluded Blacks from the political system.

Diane Nash is featured in the documentary film series Eyes on the Prize (1987) and the 2000 series A Force More Powerful about the history of nonviolent conflict and featured in the PBS American Experience documentary on the Freedom Riders. She is credited for her work in David Halberstam’s book about the Nashville Student Movement, The Children, and Lisa Mullins’ Diane Nash: The Fire of the Civil Rights Movement.

In addition, she received the Distinguished American Award from the John F. Kennedy Library and Foundation (2003),https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diane_Nash and the LBJ Award for Leadership in Civil Rights from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum (2004).

In 2013, Nash expressed her support for Barack Obama, while also sharing her misgivings about his continuing involvement in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. While encouraged by the positive implications associated with electing the first Black president of the United States, Nash still believes that the true changes in American society will come from its citizens, not government officials.

Although she attended the Selma 50th anniversary celebrations in March 2015, Nash was noticeably absent from the restaging of the 1965 Selma march. When asked about her refusal to participate in the historic event, Nash cited the attendance of former president George W. Bush. Nash, who has dedicated her life to pursuits of peace and nonviolence, declared that Bush “stands for just the opposite, for violence, war, stolen elections, and his administration had people tortured.”

Today Diane Nash remains humble and reflective.

“You have to be a whole, dignified, self-respecting person in order to be an English teacher or whatever kind of job your education would prepare you for, and I just knew that segregation was wrong, and knew that I should not be going along with it, that I should resist it. It took many thousands of people to make the changes that we made, people whose names we’ll never know. They’ll never get credit for the sacrifices they’ve made but I remember them.”

But your name, Diane Nash, is one we’ll never forget.

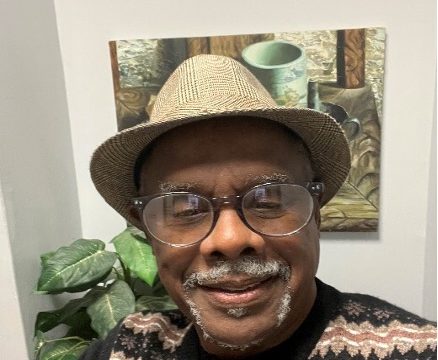

Photo: From left, Reverend John L. Edwards, Jr., Diane Nash, and John L. Edwards, III

© Terry Howard is an award-winning writer and storyteller. He is also a contributing writer with the Chattanooga News Chronicle, The American Diversity Report, The Douglas County Sentinel, Blackmarket.com, Hometown Advantage, co-founder of the “26 Tiny Paint Brushes” writers’ guild, recipient of the 2019 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Award and 3rd place winner of the 2022 Georgia Press Award.