I had best described as a “Who moved my cheese?” moment when I climbed into my car recently. Well, not “cheese” in a literal sense that’s in the title of that best-selling book, but a favorite Funch (I’ll get to him shortly) CD. You see, when I punched the ejection button, out popped that of some rap artist whose name and lyrics don’t warrant any mention here. How it got there, God (or some wayward kiddo) only knows.

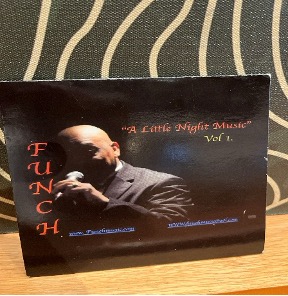

You see, what was missing was a Funch CD containing a collection of my go to music that calms me down while stuck in local traffic, mellows me out during long drives elsewhere, or prompts me to pull over, close my eyes for a listening snooze during those necessary, allow me to say, “bladder breaks.”

In a fit of panic, I searched the pocket on the side door on the driver’s side, but it wasn’t there. Next, I dumped everything out of the glove compartment and frantically sifted through current and expired registration papers, an empty Snickers candy bar wrapper, a long dead roach and a spare toothbrush. Still no luck.

Okay, if you’re wondering about my freakout over something as mundane and inconsequential as some darn CD, well I’ll give you two reasons why.

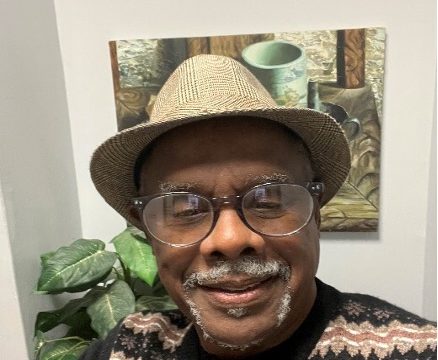

First, the missing CD is a collection of old school Soul classics sung by Mr. James Funchess, aka “Funch,” a talented singer I was raised with in a small town in Virginia. Fortunately, for him he could sing and work magic on a keyboard. Unfortunately for me, I couldn’t carry a note if it were handed to me on a silver keyboard. But that shortcoming doesn’t stop me from crooning like him when driving (always alone, mine you) and listening to his renditions of Luther Vandross’ “Dance with My Father Again,” Sammy Davis Jr’s “Mr. Bojangles,” Tony Bennetts’ two classics, “Who can I turn to,” and “Shadow of your smile,” and Louis Armstrong’s “What a wonderful world.”

My second reason is a piece written almost 20 years ago by Leonard Pitts, Jr., my go to Pulitzer Prize winning columnist for hard-hitting social insight and breath-taking prose. Add to that is the fact that before he pivoted to writing about race and culture in America, Pitts cut his teeth as a music critic among the exclusive ranks of jazz critics Whitney Balliet, Robert Christgau, Stanley Crouch and others. That’s how he met and casually “shot the breeze” a few minutes with Eddie Levert of the R&B group The O’Jays.

Almost 20 years ago Pitts wrote, “There’s Still Nothing like That Sweet Soul Music,” the opening paragraph of which cited the tragic death of young Gerald Levert, the son of talented singer Eddie Levert, himself a singer of thunderous power. On the caliber of Black music back then – and I argue continues today – Pitts further wrote:

“We live in an era where music is largely impersonal, a cut-and-paste machine tooled artifice. Moreover, we live in an era where Black music is often police blotter or a sex act or a product placement, but less frequently a love song. Still, some of us remember when Black music was about soul and soul was about truth, particularly the truth of how it is between women and men.”

Which brings me to this fact: many talented Black singers from back in the day who traveled throughout the south on the “chitlin circuit” in station wagons with trailers in tow and performed in smoke filled dance halls, attempted to “crossover” into “mainstream” music that had traditionally ignored them. Some made the transition, others who refused were not so fortunate. Many of the latter Black singers – some one hit wonders – were marginalized and forced to stay with what made them icons in the Black community while those few who did cross over had to staddle the fence between the community that made them on one side and a community that had ignored them on the other.

Saying more about old school Black music, Pitts added, “We used to call them begging, baby, baby please songs for how they promised the moon and stars to a woman if she would give you the time of the day or pleaded with broken voice and teary eyes for another chance after you fooled around and hurt her. These days, Black music produces fewer songs that cherish women. Oh, there are plenty of sex songs, plenty of I love your butt songs. But baby please is becoming a lost art.”

To Pitts’ point, many remember James Brown’s, Please, please, please,” Otis Redding’s “Try a little tenderness,” Lou Rawls’ “You’ll never find another a love like mine,” Barry Whites’ “I got so much love to give,” Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour,” Donna Summers’ sensuous “Love to love you baby,” and Mavin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing” as baby please classics.

And not to be forgotten are those classic “no dice bro” clapbacks from Black women singers during those times that highlighted the subtleties and nuances of “baby please” interactions between the two sexes back then. Esther Phillips’ “Release me, I don’t love you anymore,” and Carla Thomas’ “Tramp,” her duet with Otis Redding that exemplified the soulful repartee between Black women and men are examples that stand out in mind. And there are others.

Which brings us to a truth for many of us – a longing for the days when Black music was worth listening to and not, as it is too often today, rambling gibberish masquerading as real music to be shielded from the ears and minds of the young and impressionable.

So back to Funch, at the top of my list of my favorite of his songs, hands down it would be his rendition of “I’ll be home for Christmas” sung for many years by Bing Crosby, Dean Martin and others. You see, this one is personal given that the home Funch speaks of, the one that brings tears to my eyes when he sings it, are images of the home we both shared growing up in Virginia.

In that song he sings images of freshly cut Christmas trees on sale on parking lots while snowflakes are descending on the city. He sings images of the sweet aroma of hot dogs and burgers flowing out of Mrs. Sadie’s snack shop on Johnson Street and jam-packed gyms on Friday nights at Booker T. Washington High School just up the street. He sings images of the unique ambiences of Black churches, salons and barber shops. He sings images of bell ringing Salvation Army Santas on the sidewalk in front of Montgomery Ward. He sings images of the sounds of busy snowplows and shovels performing what shovels and snowplows were designed to perform. He sings images of overcoats, red and green scarves, leather gloves and rubber boots. He sings images of soapbox derbies, of sleds and sleigh rides. Underneath his lyrics, that’s the home Funch sings about when he sings “I’ll be home for Christmas.”

So yes, I’m unashamed of being dubbed “old school.” If that indicates that I prefer songs and lyrics that respect and elevate women – Black women in particular who inarguably are constantly being disrespected and caricatured in the media – I’ll wear that moniker as a badge of honor.

See ya next time.

Oh, wait, I did locate my Funch CD. It was underneath my front seat. Alright readers, I know what many of you are thinking about me, your bumbling columnist.

And that, ahem, is not too nice is it?

Terry Howard is an award-winning writer, a contributing writer with the Chattanooga News Chronicle, The American Diversity Report, The Douglas County Sentinel, TheBlackmarket.com, recipient of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Award, and third place winner of the Georgia Press Award.